March 26, 2020

Asylum and border management in the COVID-19 era

Report written by Jacob Bruel-Courville

Master’s student and member of the Chair, and intern at the UNHCR, Montréal

Jacob’s research focuses on irregular entries of asylum seekers to Canada from the United States.

The global spread of COVID-19 led to a progressive closure of borders, initiated by China. Justin Trudeau announced the US-Canada bilateral agreement to almost entirely close their border as of March 21, 2020. Pressured by the Conservative party, Bloc Québécois, and the Government of Quebec, the federal government announced that the border would also be closed to asylum seekers trying to reach Canada; they would be sent back to the United States. This announcement echoed critics from the media and opposition parties regarding the highly publicised irregular crossing of asylum seekers entering Canada at Roxham Road (picture 1). However, irregularity does not mean illegality. As one of the signatories of the 1951 Refugee Convention, Canada must accept any person seeking asylum in its territory. The country will decide whether they will be allowed stay or be deported after their claim has been examined by a specialised court.

However, for the past 15 years, Canada has been progressively restricting asylum seekers’ access to its territory. Since the signing of the Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) in 2004, asylum seekers transiting through the US cannot seek asylum in Canada, unless they enter irregularly. It is the Canada-US agreement that forces asylum seekers to enter into Canada irregularly. On March 21, however, the access ban was extended across the 8,891 km shared border because of the bilateral agreement. Even so, this agreement would not deter people from seeking refuge in Canada. They would rather take the risk of crossing the border at remote and dangerous places and remain in hiding once in Canada for fear of the government reprisal.

Not allowing entry of asylum seekers into Canada for health-related reasons creates a dangerous breach of the 1951 Convention, which is the only legal instrument of refugee protection. Once the principle of preventing refugees into a country on such basis is established as a precedent, other governments could implement other exceptions to achieve populist and nationalist goals.

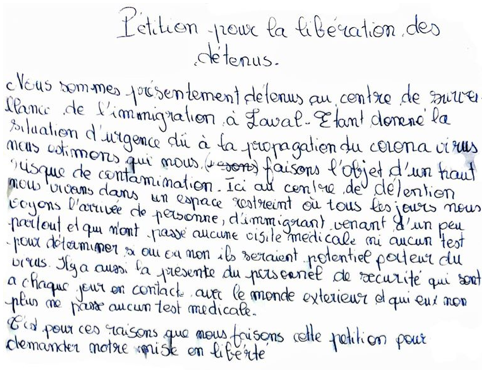

Unfortunately, the current health situation has created a precarious situation for asylum seekers transiting to Canada. Although detaining asylum seekers is prohibited under international law, various detention centres for migrants are operating in Canada. These centres, which regularly hold accompanying children, are posing a real health risk to detainees due to their close proximity and a lack of preventative health measures. On March 19th, migrants detained at the Laval Immigration Holding Centre published a petition (picture 2) asking for the authorities for provide containment measures, and, on March 24th, some detainees went on a hunger strike (picture 3) to reiterate their fear of a potential COVID-19 outbreak in the detention centre.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not put an end to conflicts, including authoritarian regimes, feminicides, persecution of those defending human rights, and discrimination against religious and sexual minorities, at the Canada-US border. As a result, migrants will keep looking for a safe place for their families and themselves, so Canada should focus on better managing these new arrivals. The country should, at least, ensure migrants’ good health when they arrive. It is better to have an irregular, but managed migration, rather than a security scheme that pushes people into unsavoury situations.